Children who possess exceptional abilities but struggle to adapt to traditional school environments: Gifted.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan has included an allocation of 80 million yen in the budget proposal for the fiscal year 2023 to address the needs of the “Gifted.” Professor Sachiyo Ishida, a renowned researcher at Chiba University’s Faculty of Education, has long been engaged in research on inclusive education* in both Northern Europe and Japan. Her proposal advocates for an inclusive education approach that encompasses “all children with difficulties” rather than segregating the “Gifted” as a distinct category.

*Inclusive Education refers to providing education that includes all children, regardless of their backgrounds or abilities. It was first defined in the UNESCO Salamanca Declaration of 1994. Inclusive education recognizes the diverse needs of children, including those with disabilities, sexual minorities, foreign backgrounds, and young caregivers, aiming to provide necessary support while ensuring education for all.

Aiming to provide support to address challenges children are facing, regardless of their disability status

―Is research on “Gifted” learners gaining popularity in Japan?

Actually, the term “gifted” is not an academically defined word. While some may envision a select few geniuses in the field of inclusive education that I specialize in, we recognize individuals who “display exceptional abilities in certain areas while also facing challenges in their school life and academics.” To capture this unique combination, we often use “Twice exceptional: 2E,” which acknowledges the dual characteristics of exceptional talent and difficulties.

In Japan’s special needs education system, children have traditionally been assessed based on the presence or absence of “disabilities,” such as intellectual disabilities and physical disabilities. More recently, there has been increasing recognition of developmental disorders as well. As a result, the need for support specifically tailored to 2E children, who possess exceptional abilities alongside difficulties, has not been well acknowledged. It is only in recent years that greater attention has been given to the challenges faced by 2E children.

While there are practical examples of 2E education worldwide, including in Japan, it can be said that systematic and comprehensive surveys and research in this field have only recently begun.

―As a researcher with over 25 years of experience studying inclusive education in Northern Europe, what do you perceive as the main challenges of inclusive education in Japan?

The challenge with inclusive education in Japan lies in its strong reliance on special needs education, where support provision is determined based on the presence of “disability.” However, true inclusive education should not draw lines based on whether a child is 2E or has a disability. Instead, it should aim to support the education of any child facing difficulties in learning, regardless of the nature of those difficulties. Embracing this broader perspective is essential to fully embody the principles and essence of inclusive education.

In addition to developmental disorders and 2E, school-age children in Japan face various other challenges. For instance, some children struggle to attend school due to parental poverty or neglect. Others might grapple with adapting to new languages and cultures when they live in a different country than their upbringing.

Educators and social welfare professionals in Japan are diligently working to address these diverse difficulties. However, there is a tendency to approach these challenges separately within different fields, resulting in a lack of organic integration. The problem lies in the disconnect between these efforts, hindering a comprehensive and holistic approach to inclusive education.

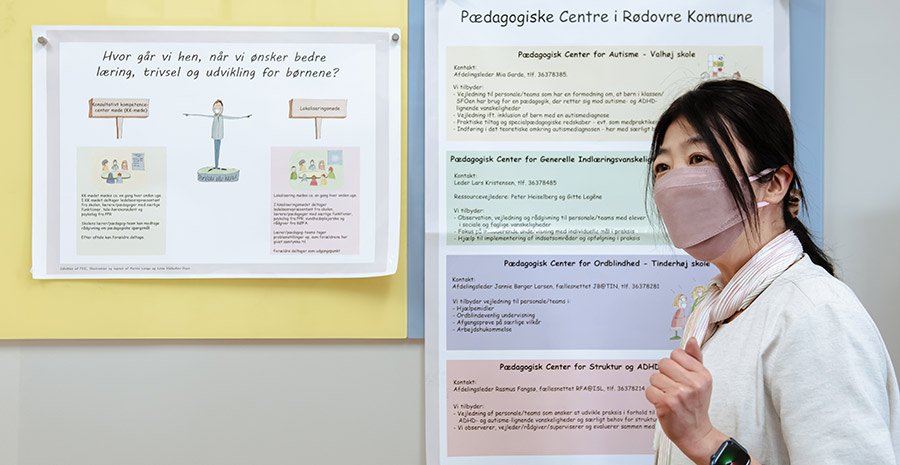

In contrast, Northern Europe differs from Japan in its approach to support, where the support is based on the presence of difficulties rather than disabilities, taking into account the child’s overall well-being.

For instance, supporting a child with a developmental disorder or school absenteeism and refusal may require significant financial resources. However, neglecting proper care during the child’s school years could lead to a lifelong dependency on social welfare support. Therefore, there is a growing understanding that providing comprehensive support to children during their formative years is more beneficial for their long-term development.

―Please tell me about the situation of “gifted education” in Northern Europe

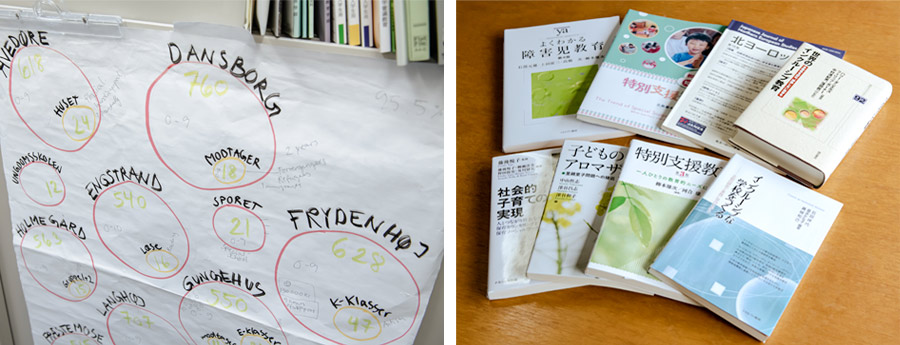

I have just started the survey; thus, I have not yet been able to grasp the complete picture or identify trends. However, I encountered fascinating stories during a recent interview with teachers and educators in Sweden and Finland.

Currently, Finland does not have dedicated classes for 2E students. In the past, they allowed elementary school students to skip grades and move on to junior high or high school. While their academic performance was generally satisfactory, there were concerns about the overall impact, as their social and emotional development might not have been adequately addressed. As a result of these experiences, Finland now adopts an approach where 2E students receive individualized instruction in subjects they excel at, while still participating in age-appropriate classes and occasionally joining upper-grade level classes. This approach appears to be yielding positive effects.

In the United States, grade skipping and acceleration are actively implemented.

There are indeed diverse approaches and solutions to the same challenges worldwide. Regarding education, the United States tends to prioritize maximizing individual abilities, even if it results in some level of disparity. On the other hand, the Nordic countries focus more on “providing high-quality education to as many children as possible on average.” In this regard, the educational approach of the Nordic countries aligns more closely with that of Japan, and there may be valuable lessons we can learn from their practices.

Northern Europe is not a “role model” but a valuable learning partner.

―Do you also conduct research at the Special Needs School affiliated with the Faculty of Education, Chiba University?

Yes, I greatly appreciate their understanding of the importance of the research and their cooperation in my investigations. Our Special Needs School has a tradition of conducting classes that enhance children’s motor skills and hand dexterity through play and everyday activities. We have deliberately designed and installed playground equipment tailored to our educational goals in both the schoolyard and classrooms. This approach enables children, including those who may face challenges in exercise or communication, to actively participate and interact with their friends while engaging in full-body exercise during play.

This spring, three Norwegian researchers visited Chiba University to observe our approach to integrating subjects and fields. While there is much to learn from their inclusive education, it is also important to recognize that they can draw inspiration from Japanese on-site practices. I believe that Northern Europe is not merely a “Role Model” to be replicated, but rather a collaborative partner in finding solutions to the common challenges faced by people worldwide. Together, we can engage in shared thinking to address these issues.

Inclusive education achieved through small ingenuity

−In Japan, where sectionalism is prevalent, it seems to be challenging to overcome the barriers between welfare and education, or to modify the rules and systems established by the government to effectively address the diverse challenges children face.

While it may be challenging to make fundamental changes to the educational and support systems, there are steps that can be taken at the local level by municipalities and other small units, as well as within schools and classrooms. For example, in the Finish cases I mentioned earlier, the collaboration between local junior and high schools enabled 2E children to participate in upper-grade level classes focused on subjects they excelled at.

Furthermore, when I recently observed a physical education class at a Japanese elementary school, I noticed a thoughtful arrangement of vaulting boxes. Instead of a simple linear arrangement based on height, the boxes were organized to accommodate students’ varying levels of proficiency. For instance, there were rows designed for students to challenge themselves in reaching greater heights, rows where they performed forward roll over the boxes, and rows where they could repeatedly practice on lower boxes if they were not proficient in jumping.

Effective class management that caters to “diverse development and varying backgrounds” is often achieved through teachers’ awareness of inclusive education.

It is crucial that teachers have the basic knowledge of inclusive education in order to implement it successfully. Nowadays, I notice that the younger generation of teachers is more attentive to the diverse needs of children, likely due to their exposure to inclusive education during teacher training courses at the university. However, I believe the current curriculum’s requirement of one credit (7-8 lectures) on inclusive education is insufficient. Recognizing the significance of this area, the Faculty of Education at Chiba University requires two credits for inclusive education and established a dedicated subject group in a course. These initiatives aim to enhance students’ understanding of inclusive education.

―Please share your plans for future research

I am planning to see the impact of SDGs on inclusive education in each country. It is worth considering the ongoing evaluation of areas that may still be lacking, despite achieving Goal 4 of the SDGs, which focuses on “Quality Education.” While Japan has been recognized for its high-quality education system, it is crucial to avoid complacency by carefully assessing the areas where improvements are still needed through the lens of the SDGs. For instance, while special needs education in Japan is relatively well-developed at the compulsory education level, there is a persistent issue of inadequate support for students after transitioning to high school.

Additionally, I would like to examine the consequences of discontinuing remote classes once the COVID-19 situation improves. While remote learning became widely available during the pandemic, schools have discontinued remote participation as the infection stabilizes. Consequently, there are instances where children requiring medical care or those who have difficulty attending school are once again facing obstacles in accessing education.

I am therefore investigating what types of educational support for students with diverse difficulties, including 2E, are necessary and how we should implement them. Together with expertise from Northern Europe, England, and Scotland, I am implementing research endeavors ranging from macro-level examination of the education system to on-the-ground efforts. The goal is to provide practical knowledge that educators can easily implement to support children with various challenges and create inclusive learning environments.

Conversely, the global number of children unable to attend school due to conflicts and other factors is steadily increasing. As an international team of researchers from developed countries, we need to contemplate our role in providing educational opportunities for these children. By leveraging our expertise and collective efforts, we aim to explore ways to ensure access to education and support for these marginalized children.

Series

Paving the Way for the Future of Children

Efforts to support the healthy growth of children are crucial. Our researchers confront the social issues surrounding modern children to protect “Children’s Present and Future.”

-

#1

2023.02.15

Children-centered support and school operations: On the occasion of the founding of the Children and Families Agency

-

#2

2023.03.10

What is “Digital Citizenship” Education that lives in a future society?

-

#3

2023.04.19

“Journey of the Brave,” a new cognitive behavioral therapy program: a solution for children’s anxiety

-

#4

2023.05.26

Examining Social Injustice of Modern Society through “Child Poverty”: Creating a Society Where Every Parent is Respected, and Every Child Thrives

-

#5

2023.06.16

Fostering Inclusive Education for the Gifted and All: Unlocking Northern European Insights for Special Needs Learners

Recommend

-

Designing Mobility: A Gentle Force in Linking People and Society

2024.02.26

-

Plant factory: sustainable plant production on Earth and in outer space

2022.10.06

-

Towards a self-sustainable natural environment: The science of restoration ecology, where researchers engage in conversation with the earth

2023.02.02