Detailed experiments provide new insights into the forces and mechanisms that influence polymer micelle formation and gelling behavior

Micelle-forming polymers such as poloxamer 407 (P407) are promising drug nanocarriers, yet their sol–gel transition under physiological conditions remains poorly understood. In a recent study, researchers from Japan experimentally analyzed how P407 micelles interact in saline environments mimicking bodily fluids. Using advanced X-ray and light scattering techniques, they shed light on key inter-micellar interactions and structures that influence gelling behavior, providing crucial insights for future drug nanocarrier design.

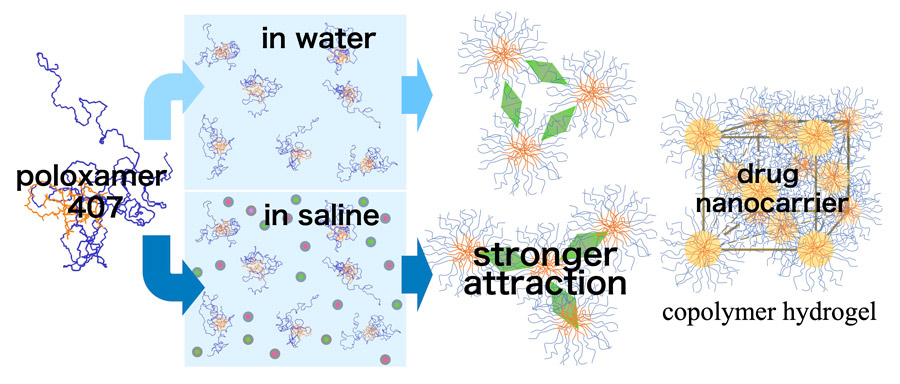

Image title: Differences in gelling behavior of poloxamer 407 depending on solvent

Image caption: Poloxamer 407 self-assembles into micelles in solution and turns into a gel at around body temperature. This study revealed important differences in how these micelles interact and organize into gels depending on the salts and ions present in the solution, which could ultimately affect key properties for drug nanocarrier technologies like the drug release rate.

Image credit: Dr. Takeshi Morita from Chiba University, Japan

Source link: N/A

Image license: Original content

Usage Restrictions: Cannot be reused without permission.

Polymer micelles are tiny, self-assembled particles that are revolutionizing the landscape of drug delivery and nanomedicine. They form when polymer chains containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments organize into nanoscale spheres in liquid solutions; these structures can trap and hold drugs that are otherwise difficult to dissolve. Poloxamer 407 (P407), a widely studied micelle-forming polymer, is particularly useful because it changes from a liquid into a soft gel as it warms, becoming most stable near body temperature. This temperature-dependent gelling behavior allows P407 to slowly release loaded drugs over time, thus reducing dosing frequency and their side effects.

Despite extensive laboratory research, scientists have struggled to fully understand P407’s sol–gel transition. Its peculiar properties do not come from individual micelles acting alone, but from how they interact and arrange themselves together. However, most existing knowledge is based on experiments in pure water, which is far simpler than the liquid environments found in the human body. On top of this, existing theoretical models rely on assumptions that do not work well for polymer micelles, leaving key inter-micellar forces unclear and difficult to predict in laboratory saline solutions that mimic bodily fluids.

To tackle these knowledge gaps, a research team led by Associate Professor Takeshi Morita from the Graduate School of Science, Chiba University, Japan, conducted an in-depth experimental study on how P407 micelles interact in a saline environment. Their paper, made available online on December 9, 2025, and will be published in Volume 707 of the Journal of Colloid and Interface Science on April 1, 2026, was co-authored by Mr. Shunsuke Takamatsu, Dr. Kenjirou Higashi, and Ms. Minami Saito, all from Chiba University; Dr. Hiroshi Imamura from Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology, Japan; and Dr. Tomonari Sumi from Muroran Institute of Technology, Japan.

Rather than assuming anything about how micelles should behave, the researchers used experimental data to quantify their interactions under conditions that closely resemble those inside the body. They focused on P407 micelles dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), a standard solution used in biological research, and combined two complementary techniques. First, small-angle X-ray scattering was used to probe how micelles are positioned relative to one another over nanoscale distances, revealing collective structural patterns. Then, they used dynamic light scattering to measure the sizes and motion of individual polymer chains, micelles, and larger aggregates by tracking fluctuations in scattered light.

By integrating these datasets, the researchers calculated the ‘pair interaction potential,’ a quantitative description of how strongly two micelles attract or repel each other depending on their separation. They found that as the temperature increased toward gel formation, micelles became more regularly spaced, moving slightly farther apart yet still remaining connected. This behavior is consistent with an entropy-driven process known as the Alder transition, in which particles crystallize because an ordered arrangement allows more freedom for small thermal motions. However, in PBS, the attractive forces between micelles were stronger than in water, meaning they tended to bind more tightly. This stronger attraction limited how far micelles could separate, producing a gel with more structural fluctuations and less uniform order.

The team demonstrated that these differences had marked effects on gel stability. Gels formed in saline broke down at lower temperatures than those formed in water, suggesting that structural fluctuations weaken the gel as temperature rises and make it collapse sooner. “With this improved understanding of inter-micellar interactions that govern drug nanocarrier properties, it will be possible to elucidate and predict the fundamental mechanisms of sustained drug release behavior and gelation in environments closer to bodily conditions,” states Dr. Morita.

The findings of this study have important implications for drug delivery research. Polymer micelles like P407 are widely studied as promising carriers for novel drugs, including many modern anticancer and anti-inflammatory compounds. Understanding how salts and ions affect micelle interactions could help researchers design formulations that release drugs more predictably and remain stable at body temperature. “By advancing our knowledge of micelle behavior under physiological conditions, our work will help advance drug nanocarrier research, enhance the pharmacological efficacy of poorly soluble drugs, and contribute to the development of technologies that reduce the physical and psychological burden of taking medications,” concludes Dr. Morita.

Beyond the specific micellar system of P407, this work demonstrates how experimentally grounded approaches can clarify interactions and physical mechanisms in complex soft materials—an essential step toward translating nanoscience into practical applications.

To see more news from Chiba University, click here.

About Associate Professor Takeshi Morita from Chiba University, Japan

Dr. Takeshi Morita obtained a PhD degree in 2000 from Chiba University, where he currently serves as an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Science. He specializes in nanomaterials, nanostructural chemistry, and physical chemistry, with a focus on mesoscopic structures and structural fluctuations in nanoscale systems, elucidated through detailed experimental and analytical techniques. He has published over 80 papers on these topics.

Funding:

This work was supported by a JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI, Grant No. 23K23156).

Reference:

Title of original paper: Clarifying pair interaction potential between poloxamer 407 micelles solvated into phosphate-buffered saline in sol-gel-sol transition

Authors: Takeshi Morita1, Shunsuke Takamatsu1, Hiroshi Imamura2, Minami Saito3, Kenjirou Higashi3, and Tomonari Sumi4

Affiliations:

- Graduate School of Science, Chiba University, Japan

- Department of Biological Data Science, Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology, Japan

- Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chiba University, Japan Graduate School of Engineering, Muroran Institute of Technology, Japan

Journal: Journal of Colloid and Interface Science

DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2025.139642

Contact: Takeshi Morita

Graduate School of Science, Chiba University, Japan

Email: moritat@faculty.chiba-u.jp

Academic Research & Innovation Management Organization (IMO), Chiba University

Address: 1-33 Yayoi, Inage, Chiba 263-8522 JAPAN

Email: cn-info@chiba-u.jp

Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology

Address: 1266 Tamura, Nagahama, Shiga 526-0829 JAPAN

Email: kouhou@nagahama-i-bio.ac.jp

Muroran Institute of Technology

Email: koho@muroran-it.ac.jp

Recommend

-

The Global Goal of Carbon Neutrality by 2050 (Part 1): Universities as Agents of Change

2023.07.12

-

A Day in the Life of a Sports DoctorProfessionals behind the world’s most prominent sporting events

2023.04.13

-

Affecting behavioral changes through a combination of mind and body: How can we calmly cope with stress in the event of a disaster?

2023.02.27