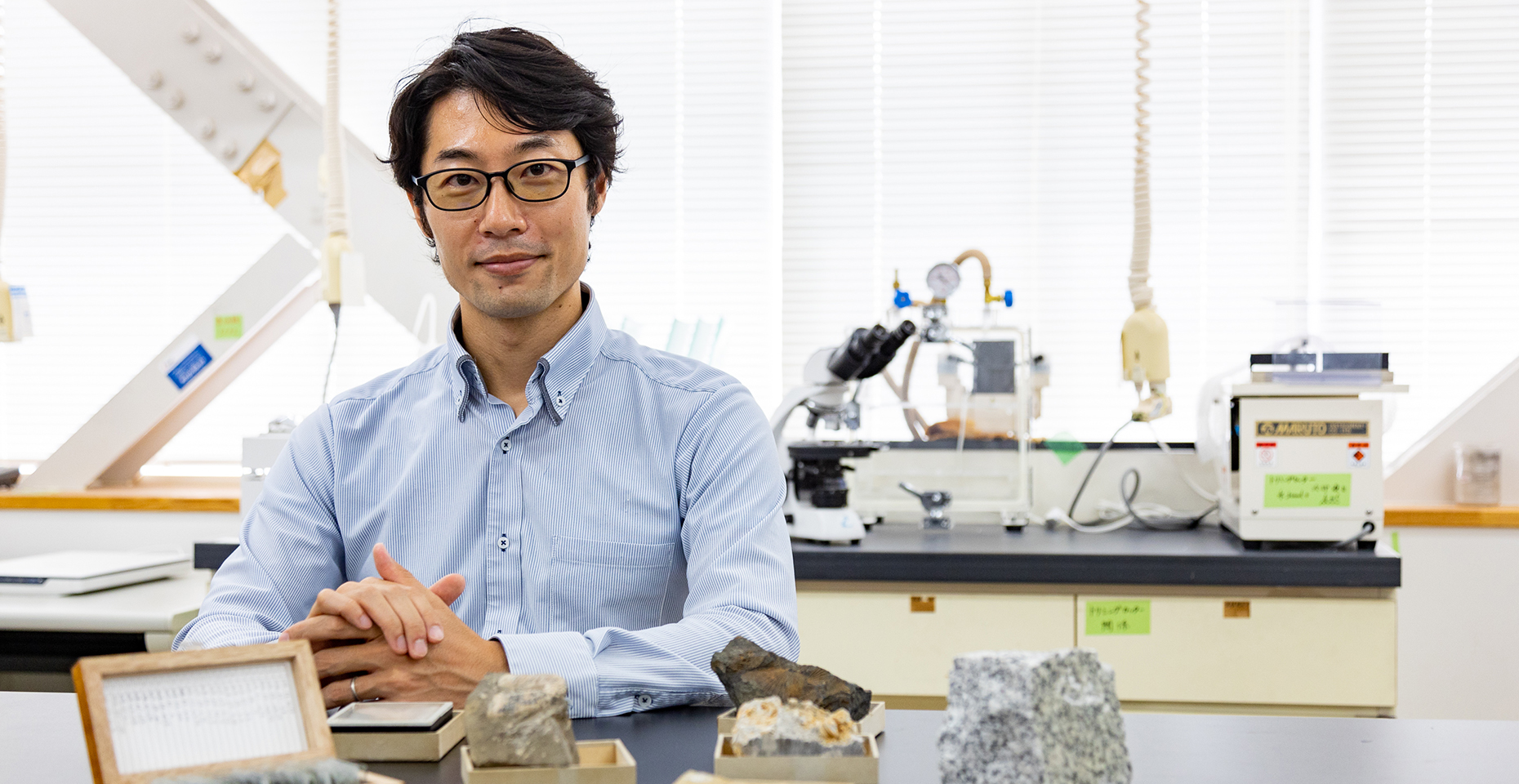

Did you know that there is a researcher who happily calls himself “Dr. Fossil Poop”? His name is Kentaro Izumi, an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Education, Chiba University. Dr. Izumi is an up-and-coming paleontologist who researches “Trace Fossils,” which are the remains of the activities of ancient creatures, to study their ecology and the global environments in which they lived.

Dr. Izumi’s work has been highly praised for its creativity, and his ability not to be limited by conventional methods. For this, he was awarded the Chiba University Award for Distinguished Researcher in the academic year 2022. He has also been active on a team researching the Chibanian age (previously, the Middle Pleistocene). Surprisingly, his fundamental fighting spirit was cultivated during his struggle with his feelings of inferiority and through his sports cheering-squad activities. In a 90-minute interview with Dr. Izumi, we gained a deeper understanding of his strategies for survival in the competitive world of research, which were borne from his earlier experiences.

A completely different world from today: How Dr. Izumi was attracted to the ancient Earth at a very young age

Before he knew it, he was enchanted with the ancient Earth

Kentaro Izumi relays his story, ‶My earliest memory relating to my current research is of an illustrated reference book. Such books introduced a variety of themes, including fish, insects, etc. I still have a clear memory of the wonder I felt when I first looked at an illustrated book that showcased the history of the Earth and the history of life on Earth. How excited I was to learn that the ancient Earth and organisms were completely different from today! Before I knew it, my thoughts were filled with the ancient world.

For the same reasons, I also loved Japanese and world history. I did not have a kind of obsession with fossils, however. In fact, before university, I had never experienced a fossil dig, and I never even saw the film, Jurassic Park. When I reached my fourth year at university, I wasn’t sure what to say when my supervisor asked what I wanted to focus on in my graduation thesis.

The first thing that came to mind was ‘dinosaurs,’ which is by no means a unique theme. My supervisor said that that might require overseas travel, as many of the dinosaur fossils were found in strata outside Japan, and thus those areas were more advantageous for research. So I immediately gave up on dinosaurs. I was so busy on the University of Tokyo cheering squad (Ouen-bu) that I enjoyed spending my days in the Tokyo Big6 Baseball League and others.

I was convinced that I had to do my best at cheering because I might never have the opportunity again. I, therefore, wanted to pursue research that I could do in Japan. My supervisor at the paleontology lab I was in during my fourth year proposed several themes for my graduation thesis. There were three types: working in a lab performing chemical analyses of fossils, theoretical research involving numerical models, and outdoor research, which meant chiefly field surveys. I had a vague idea that the first two were not my forte, so I followed my intuition and chose fieldwork. By the way, I do all three kinds of research today.”

Sublimating “inexperience” into originality

Dr. Izumi chose the Lower Jurassic strata (183 million years ago) in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, for his graduation thesis research simply because he had never been there.

Kentaro Izumi continues. “I really enjoyed my first time in the field. The condition of the strata at the site was so poor that even the graduate students sympathized with me. Yet because it was my first time, and I had no prior expectations, I just accepted that as kind of normal.

So, if I had been crazy about fossils, I might have had higher expectations, and that would have ended in disappointment. I began to think that I would find some things I didn’t know about and use my lack of knowledge as a kind of strength, an impetus. Of course, I also enjoyed success because of the great physical and mental power I had gained from my cheering activities over my four-year university life.

I left the cheering squad when I entered graduate school, and all that time and physical and mental strength were poured into my research work, which I dedicated myself to daily. I certainly felt different from my fellow students in that I had not been crazy about fossils, and also due to my full dedication to my squad activities during my entire undergraduate life. That was another reason why I had to put all my efforts into my research.“

Exploring uncharted waters

During my graduate school years, my supervisor asked if I would like to accompany him on a trip to Germany. There, we would work on the Lower Jurassic strata. The supervisor knew about my graduation thesis, and I suppose he thought it would be a good theme for my Master’s thesis to compare the Japanese strata with the German strata.

I knew, though, that Germany was a country with a 150-year history of fruitful work in geology and paleontology. Fossils found at the site had already been studied in considerable detail. When I realized all that, I thought it would be impossible for a Japanese graduate student to make any discoveries there. I was really caught in a dilemma.

I worked hard before going to Germany to find an area that had not been worked on before. I thought, well, the bones of creatures have been thoroughly studied, but almost no research had been conducted on trace fossils. At that site in Germany, fossils of fecal pellets excreted by marine invertebrates had been relatively neglected.”

When asked why he was able to look at his situation so objectively, Dr. Izumi had a surprising response.

“It was my inferiority complex. From my elementary school years onwards, I was surrounded by superior students, and I knew I couldn’t compete. In fact, it seemed that everywhere I went, everyone I met was so incredibly intelligent.

Later, when I knew I wanted to work as a research professional in paleontology, I wouldn’t try to compete with them in the same area where there was little chance of success and me underperforming’—instead, I would tackle a different area where I myself could excel. In fact, that was the same reason I joined the cheering squad. I was aware of my inferiority complex. I, therefore, set goals that I could accomplish to grow at my own pace.

Now, if I had been a person who always thinks logically, I would have said my chances for success were low, and my tendency might have been to avoid action. Yet, in my cheering squad days, I did a lot of things that many people might find meaningless. But, so many times, those little things have later been linked with great and meaningful experiences for me. If you have no preconceptions, you just might decide to delve into something with curiosity and interest, even if others might believe them to have no meaning. That’s the kind of spirit I inherited from my cheering-squad life.

So, in paleontology, we make hypotheses about the ancient Earth and its creatures based on just a few excavated fossils. We then try to prove or disprove them. In this field, one can compete on the basis of a single good idea, and that suits me quite well. “

Integrative Paleontology: The Emergence of Biogeosciences

To expand his research, Dr. Izumi has recently valued interdisciplinary exchanges.

“Recently, I have been active in joint research with biologists. So, maybe it’s because they deal with living creatures, but when we talk about fossils, they ask me questions that someone in the field might never think of, such as ‘Tell me about the life history of that creature. What was its lifespan? What color was it? Is this a male or a female?’ And so on.

It’s not rare to make a huge discovery of just a single fossil, and, in an extreme case, one speculates on phenomena based on a single sample. Of course, this cannot be helped since the number of samples tends to be low, but the fossils you dig up may be of an individual creature that is completely far from the average individual of the groups. That is, your fossil may not be a representative example of an ancient creature. You can imagine from observing people and other living creatures today that there are large differences, even within a single species, in their developmental stage, between males and females, due to habitat environments, and so on.

In biology, you generally engage with multiple individuals of a single species, and you can observe living organisms. But it is evidently impossible to see the living organism in the case of paleontology. You must make the best possible estimates. Thus, I began to feel that there are limitations to how much one can learn if one focuses only on the fossils themselves. You can, for example, research currently living creatures from the perspective of paleontology, or you can use the theoretical approach, based on numerical models, to infer the behavioral mechanisms of ancient creatures. So, here, it is important to expand one’s views such that paleontology actually becomes a kind of Biogeosciences. However, when I compare this image of what my research could be, to what it is today, it is clear that a rocky road lies ahead, and it is a road I have to rumble over each and every day.

So I have started studying the poop of currently living creatures, doing ‘breeding’ experiments of marine benthos, constructing new numerical models, and performing research based on environmental DNA. I make some daily progress in each of these areas.

For me, paleontology, and earth life sciences, are academic fields where the more you study, the more unexplored areas you find. In this sense, they are really unending.”

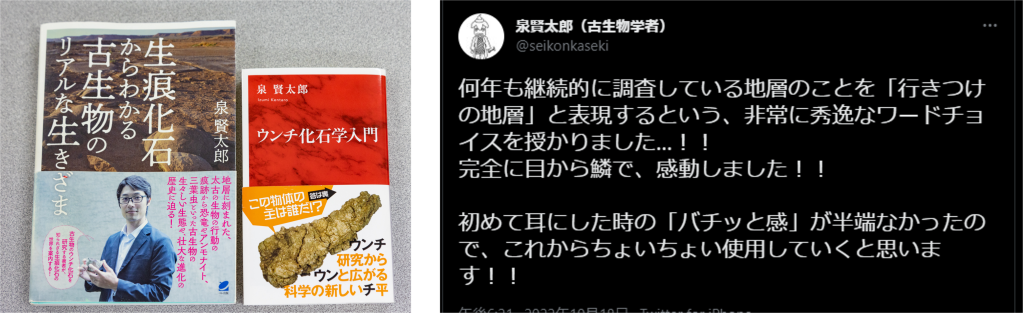

Finding time in the midst of his busy work, Dr. Izumi has published the highly acclaimed book, Introduction to Fossil Poop (Coprolites). He is also active on Twitter, tweeting in Japanese using the hashtags #古生物学者の1日(A day in the life of a paleontologist) and #古生物学者あるある (Things paleontologists do)

Dr. Izumi says, “I think there are a lot of children who are really interested in fossil research, but very few students choose to study paleontology at university and thereafter. Maybe one reason is that there is not enough information out there about the career of a paleontologist. Maybe more students would enter a paleontology lab if they knew more about the daily life of researchers and about our real world. That’s why I have written a really fun book for interested beginners, and I continue to use Twitter and other social media to try to get the message out there.”

Recommend

-

Solving Real-World Healthcare Challenges: The Power of Medical-Engineering Collaboration in Research and Education

2023.03.23

-

Unveiling the Truth of the Universe through Simulated Catalogs: Unleashing the Power of a Theoretical Telescope, ‘Supercomputer’

2023.08.07

-

Functioning of Biological Diversity: Lessons from Ecology on the Importance of Minority Perspectives

2023.06.15