Originally published on June 6, 2022, this article was subsequently updated on July 7, 2025, to reflect the latest available information.

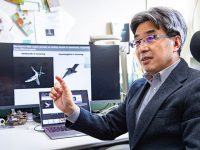

Dr. Akimasa Nakano, a professor at the Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University, dons many hats—a former senior official at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, a vegetable sommelier, and a picture book author. Dr. Nakano’s ambition is to stimulate agricultural innovation through smart agriculture as a team. We interviewed Dr. Nakano, a key person in the industry-academia-government collaboration, about his passion for agriculture.

All-around player: technology, production, and field practices

What motivated you to get involved with agricultural research?

I come from a farming family in Ube City in Yamaguchi Prefecture. As such, farming has been a part of my life since I was born. Around 1985, when I had to choose a career path, there was a worldwide movement to tackle the problems of hunger and poverty in Africa. The song “We Are the World,” which expressed support for Africa, was a musical hit back then. I became interested in biotechnology because I was inspired by the notion that I, too, could solve the global food crisis through it.

However, the more I learned about agriculture, the more I realized that farming in Japan faces many challenges. The number of farmers here is decreasing, the population is aging, and the farmers earn little profit for the hard work they put in. I wanted to change this trend. So, I decided to work for a research institute within the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries with the aim of improving the agricultural industry from the bottom up. I hoped to accomplish this by establishing a broad framework involving policies, subsidies, and R&D.

The mood at the time was encouraging research that would be useful in the field, so I naturally prioritized developing technologies that are easy to use in the field. By balancing my work between the research institute, government agencies, and hands-on farming, I acquired a broad perspective that helped me understand what is needed in each area—technology, policy, and field applications.

‘Smart Farming’— A Dramatic Change in Agriculture, from Physical Labor to Brain Labor

What is “smart agriculture?”

Smart agriculture is a new type of agriculture that incorporates state-of-the-art technologies, such as robotics and information and communication technology (ICT). As I mentioned earlier, the profit margins are low in conventional farming. So, to increase income, it is essential to increase productivity. As shown in the equation below, to increase productivity, we just need to increase the yield and quality and decrease labor hours.

Productivity = (Yield ✕ Quality) ÷ Labor hours

Smart agriculture improves all three of these parameters and contributes significantly to productivity. Smart agriculture, where productivity can be increased and a decent profit can be earned, has great potential to boost the number of new farmers. This can greatly benefit agriculture. Technology can be used to digitize the skills and knowledge of skilled farmers so that their skills can be digitally inherited by future producers. High levels of farming skills will no longer be necessary, and the industry will shift from grueling physical labor to “brain labor” that makes full use of information technology. We anticipate that more people from other industries, as well as young people, will enter farming.

Will farmers be left behind if they do not have access to advanced IT?

Not really. However, it is certainly true that new technologies can improve production efficiency. When you hear the term “smart agriculture,” you may imagine that everything is computer-controlled, like in science fiction. Still, even the automation of very simple daily tasks, such as watering and ventilation in greenhouses, is a form of smart agriculture. There is a good chance that seemingly unrelated technologies owned by private companies can actually be utilized in smart agriculture. I would be happy if academia and industry could work together to give shape to our ideas and further promote smart agriculture.

Reducing workload in cherry tomato cultivation

Why is cultivating cherry tomatoes so labor-intensive?

I have been studying tomato cultivation for about 30 years. Among the different varieties, cherry tomatoes are one whose production has dramatically increased in recent years in Japan. Thanks to their vivid color, it is a common practice to add them to bento (lunch boxes) in Japan to make the meal more attractive.

However, harvesting cherry tomatoes is very time-consuming and labor-intensive. These small vegetables have to be harvested by hand and checked individually to ensure they are at the right stage of maturity.

Moreover, the thinner the skin of the tomatoes, the more palatable they are. But these thin-skinned tomatoes are prone to splitting. Because split tomatoes cannot be shipped, they must be manually removed. Fruit splitting often occurs when the fruit surface gets wet or if harvesting is delayed. If splitting happens during the distribution process, there’s an increased chance of mold and bacteria, as well as other problems.

How can smart agriculture solve these challenges?

To boost efficiency, we switched from harvesting these tomatoes individually to harvesting them in bunches (like bunches of grapes). However, as some varieties of cherry tomatoes lack synchronized ripening, farmers have to wait for all the fruits to ripen, which can lead to fruit splitting. To overcome this problem, we are developing varieties that ripen at the same time, have less fruit splitting, and are suitable for bunch harvesting. Another challenge is that the robot cannot find and harvest the fruit if leaves cover it. So, we have also explored environmental controls and cultivation systems to suppress excessive leaf growth. We are further upgrading harvesting robots and investigating optimal logistics and packaging systems.

Furthermore, as a new initiative, I am now promoting empirical research on cultivation techniques that effectively integrate robots with production technology. This work is being conducted in collaboration with a startup company at the Biohealth open Innovation Hub (BIH)*, newly established by Chiba University on its Kashiwanoha Campus in May 2025. In addition, I am working on the development of multifunctional robots to support the next generation of agriculture.

BIH: The Biohealth open Innovation Hub is a new platform launched by Chiba University to foster collaboration and innovation among universities, companies, and local communities in the fields of bio and health.

My motto is “Fostering global well-being through horticultural innovation.” Even if each improvement is small, we can collect and build upon these improvements to create a significant innovation. That is why I am so committed to collaboration.

I have interacted with many companies, researchers, and producers. I am in charge of orchestrating this network of connections to place the right person in the right position and create a successful team.

Picture book and space horticulture

Please tell us about the other cutting-edge agricultural research you are involved in

Together with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Dr. Goto of Chiba University’s Graduate School of Horticulture, we are exploring the possibilities of space horticulture. I am in charge of the research on the recycling of waste in space. Farming in space must produce no waste and, at the same time, reuse resources as much as possible. It is the ultimate zero-emission, recycled environment. While this is a space horticulture project, the technologies developed are also highly relevant here on Earth. In fact, through a collaborative research initiative involving Chiba City and universities, I am developing technology to utilize sewage sludge generated in Chiba City for horticultural crop production. I remain committed to practical research that can be easily converted to field applications.

Could you tell us about your work as an author of picture books and as a vegetable sommelier?

I authored a picture book for elementary school students—the next generation—to help them understand the importance of a safe environment and the importance of food in sustaining human life. The “Nekko no Ehon” (Picture Book of Roots, supported by the Japanese Society for Root Research) allows children to flip over the root part in the drawing of a plant and see what is in the soil. Even small children who cannot read can enjoy this book. For elementary and junior high school students, I have also published a four-volume series on plant roots, as well as a four-volume series on sustainable agriculture, forestry, and fisheries.

When I worked at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, I used my long commutes between Kasumigaseki and Tsukuba to plan and develop numerous book projects. I decided, “Since I can’t do experiments during the commute time, I’d get on with my writing instead.” I have always enjoyed “what I can do now” rather than regretting what I cannot do. That mindset hasn’t changed, even after joining Chiba University.

I obtained the Vegetable Sommelier and Soil Doctor certification in order to learn more about vegetables and soil. Then, an unexpected thing happened. Among my colleagues who had obtained the highest certificate, “Advanced Professional Vegetable Sommelier,” there were a frozen food consultant and a technician at a seed company. If I had not studied to obtain the sommelier certificate, I would never have met people from such diverse backgrounds, nor would my network have expanded so greatly. I have been fortunate enough to enjoy my work, and the scope of my work has expanded as a result.

Making Kashiwanoha Campus a hub for promoting public relations of R&D

The Kashiwanoha Campus—where my laboratory is based—is located between Tokyo, the hub of commerce, and Tsukuba, the center of research. I believe that by showcasing our technologies, such as a harvesting robot, we can position our campus as a satellite research hub of Tsukuba, and it will enhance the recognition of our research and promote companies involved with our research. Personally, I hope to help develop Kashiwanoha Campus into a platform for the industry-academia-government collaboration in food and horticulture, leveraging its strategic location. At BIH, I will further strengthen collaboration and accelerate the dissemination of food and agricultural technologies.

Please tell us about your future research plans.

Great innovations occur when knowledge meets new technologies. For this to happen, first, we need a place where new information can accumulate. I believe that is the role of a university. At universities, we can pass on our experiences to the young people who will create the future. I joined Chiba University in 2020, with the intention of dedicating the remainder of my career to nurturing talent and developing skills in the next generation. Through these efforts, many collaborations have emerged, leading to research and technological development aimed at addressing major challenges such as sustainable agriculture, climate change, and labor shortages in the agricultural sector. Seeing many of the graduates who participated in these projects now thriving in related fields affirms my belief that this is exactly why I came to the university.

While the majority of the people in academia are specialists, I consider myself something of a generalist. Taking advantage of my broad knowledge and the new BIH, I hope to continue advancing competitive, future-oriented agriculture and help build a shared base of expertise at Chiba University—Japan’s leading institution in horticultural science.

Series

Horticulture Innovation −Creating the Future of "Food" and "Greenery"−

Chiba University is the only national university that accommodates a department of horticulture in Japan. We highlight our researchers who are exploring the possibilities of Food and Landscape.

-

#1

2022.09.27

Fostering Global Well-being Through Horticultural Innovation

-

#2

2022.10.17

Making the Invisible Visible: Drones Enabling Agricultural Advances

-

#3

2022.11.07

Designing a world-class climate-resistant fruit!~Developing “Designed Grapes” for Custom-Made Wine to Commemorate Special Occasions

-

#4

2023.02.02

Towards a self-sustainable natural environment: The science of restoration ecology, where researchers engage in conversation with the earth

-

#5

2023.05.19

The reciprocity of life: The interactive relationships between people, plants, and the environment