Note: All affiliations, titles, and company information are current as of the time of the interview.

On social media, Professor Eiryo Kawakami humorously introduces himself as a ‘Triple Dr.’ —a medical doctor (Dr.), a PhD holder (Dr.), and a drummer (Dr.). Behind this playful self-introduction lies a serious mission: advancing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data science technologies for the early detection and prediction of disease. Professor Kawakami serves as the Director of the Center for Artificial Intelligence Research in Therapeutics, while also playing a central role in the management meetings of the Chiba University Data Science Core (DSC). Balancing these responsibilities with his research and personal interests makes for a busy but stimulating life.

“I enjoy intellectually exploring in many different directions,” he says. We spoke with him about his vision for the future of medicine powered by AI.

To the Medical School: Seeking Clues for AI Research from Human Neurons

It’s rare in Japan to find an AI researcher who holds both a medical license and a PhD. What led you to your current research?

I was good at math in high school and even competed in the Mathematical Olympiad. However, one exceptionally talented peer prompted me to explore a different path. Even so, I have always enjoyed mathematical thinking, which is why AI caught my interest. Around 2000—the so-called ‘AI winter’*—there were hardly any research labs in the field.

I, therefore, entered medical school with the vague idea that studying the human nervous system might eventually lead to AI-related research. Because of this, even after obtaining my medical license, I never considered pursuing clinical practice.

Around the time I graduated, I became interested in data-driven research. I first worked on analyzing viruses, then yeast and mouse cells, and in 2016, I began working with real-world human data. However, I quickly realized that human data varies greatly from person to person, and the analytical methods I had used on experimental animals were largely ineffective. That led me to incorporate techniques such as machine learning (ML), which allowed me to handle a wide variety of human data—and that’s the path I have been on ever since.

*AI Winter: AI research has historically gone through cycles of hype and stagnation. Periods of high expectations for technological breakthroughs are often followed by times when the limitations of the technology become apparent, leading to reduced funding and slowed research. The period around the year 2000, when AI research experienced particularly low activity, is commonly referred to as the ‘AI Winter.’ Since 2022, interest in AI has surged again, making what some call the ‘AI Spring,’ the fourth major boom in the field.

AI-based disease classification and prediction

One of your research themes is ‘Disease stratification and onset/prognosis prediction with AI.’ Could you explain what this involves?

Current medicine is largely limited to making decisions at a single point in time: doctors assess a patient’s condition and decide on a treatment plan based on clinical guidelines and their own experience. However, by leveraging AI techniques such as ML, we can develop medical systems that determine treatment plans while also predicting future disease progression.

A single disease can often be classified into multiple subtypes, with the expected course and optimal treatment varying accordingly. This raises the question of whether current human-based classifications are truly appropriate. By applying ML, we can objectively verify and potentially refine these classifications. One of the main focuses of my research is the development of underlying methodologies for this approach, called ‘disease stratification.’

Can you give us an example of how disease stratification works?

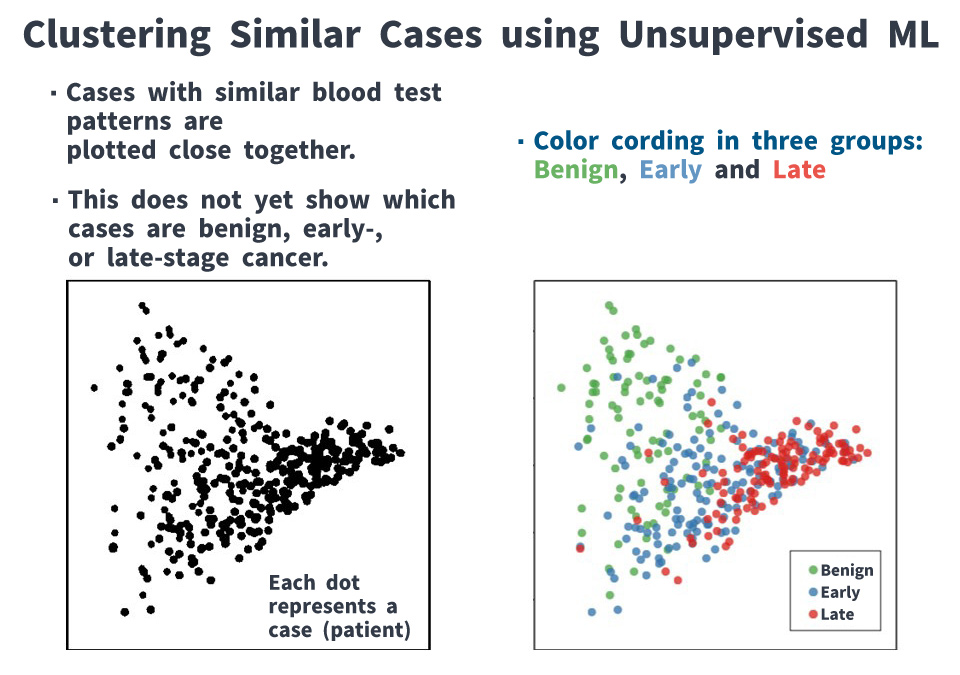

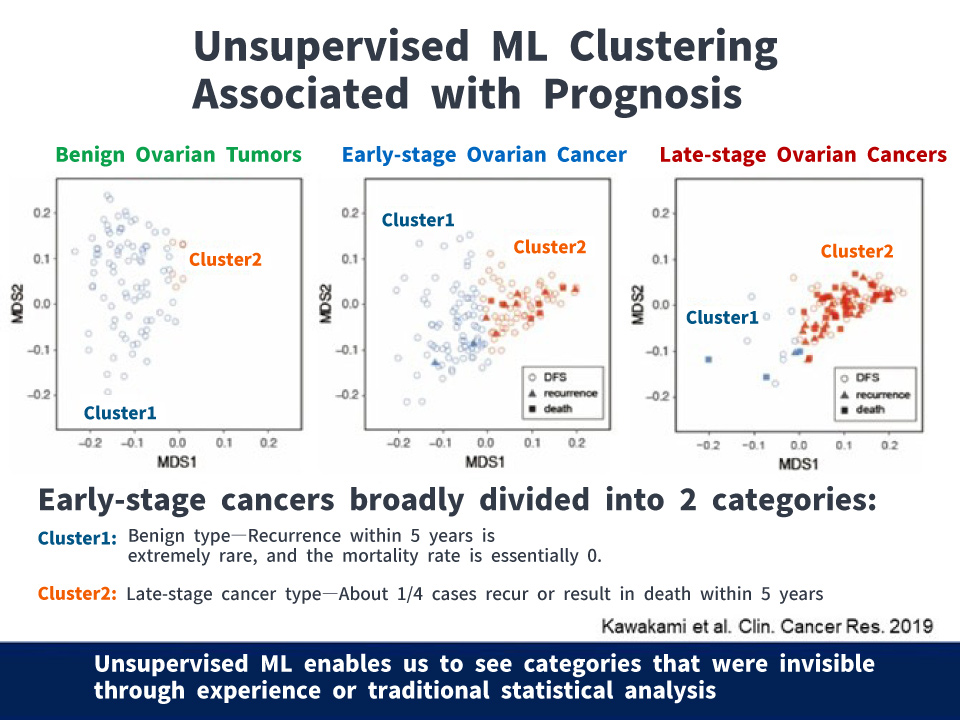

We attempted to predict whether ovarian tumors were benign or malignant, and for malignant cases, whether they were early-stage or late-stage, using pre-surgery blood test data. With supervised ML*, we achieved 92.4% in distinguishing benign from malignant tumors. However, the accuracy for classifying early- versus late-stage cancers was only 69%, making this approach unsuitable for clinical application. This relatively low accuracy is likely due to the similarity between certain early- and late-stage cases, which makes reliable differentiation challenging.

Then, by grouping cases using unsupervised ML*, we found that early-stage cancers could be broadly divided into two categories: those resembling benign tumors and those resembling late-stage cancers. Furthermore, about one-quarter of late-stage type were identified as having the potential to recur or cause death within five years. This suggests that among early-stage cancer cases, some are biologically closer to late-stage cancers, underscoring the need for appropriate treatment.

*Supervised ML: By training a model on a large dataset prepared in advance with correct labels, it becomes possible to make accurate predictions and classifications even for new data.

*Unsupervised ML: Analyzing the inherent structure and patterns of data without prior labeling is useful for tasks such as grouping and simplifying data.

This could ultimately redefine diseases themselves. Can AI also be applied to predicting the onset of diseases?

That’s right. For example, we are conducting research to detect early signs of disease by comprehensively analyzing data from wearable devices such as smartwatches and smart glasses, as well as molecules found in saliva.

In many cases, there is not a simple one-to-one relationship between a specific marker and a disease—for example, a certain value rise does not automatically mean a patient will develop that condition. Instead, multiple factors interact with each other. In other words, living organisms function as networks, and it’s necessary to view them as a whole system rather than isolated parts. In such cases, we sometimes use Transformer*, a type of deep learning model, for our analysis.

* Transformer: A technology developed by Google researchers in 2017 that forms the foundation of ChatGPT. It calculates the relationships among data elements, such as words in text or signals in speech, and identifies the most important information. This allows for context-aware interpretation and has demonstrated high performance across a wide range of fields, including natural language processing.

What are the biggest obstacles to applying AI in real-world clinical settings?

One major challenge is the lack of time-series data. For example, a single blood test taken at one point in time is not sufficient; both long-term blood test data and information about the patient’s pathological condition at the time of blood collection are needed.

An issue unique to Japan is that each medical institution uses a different format for electronic medical records, which makes data integration difficult. It is also necessary to develop ML methods that can handle these varying formats.

Japan’s first AI center affiliated with a medical school

As a Director of the Center for Artificial Intelligence Research in Therapeutics, what do you consider the center’s main strengths and defining characteristics?

The center was established in 2018 as Japan’s first AI research center affiliated with a medical school, and I have served as its director since 2019. Being the first center of its kind in Japan, one of its key strengths is that it has been able to attract many talented researchers.

A defining feature of the center is its focus on ‘Therapeutics.’ While much of current medical AI research is geared toward diagnostic imaging, our center emphasizes treatment and prevention. We actively collaborate with clinicians, launching numerous projects and publishing the results of our work.

Working with researchers from various disciplines and roles must be challenging. How do you handle communication?

That’s true. Typically, AI researchers aren’t very familiar with medicine, and medical researchers don’t have much experience with AI. However, at our center, we have created a system that allows researchers from different fields to come together and discuss issues collaboratively. Another notable feature of the center is the speed at which we take concrete action—often within just one month of identifying an issue.

Launching Data Science Core: Consolidating Resources and Translating Roles in Collaboration

You are also a member of the steering committee for the Data Science Core (DSC), launched in 2024 as one of the university’s strategic initiatives. Could you tell us more about the DSC?

The DSC promotes the shared use of equipment and technology across the university. For example, it consolidates resources that are commonly needed by many laboratories—such as next-generation sequencers, mass spectrometry equipment, GPU servers, and bioinformatics expertise and personnel—with the aim of raising the overall level of research at Chiba University.

It also serves as a contact point for companies interested in industry-academia collaboration with Chiba University researchers. The DSC Director, Dr. Hiromu Nishiuchi, who also runs his own company, has established a system that enables appropriate negotiation of terms for such collaboration.

You engage in many collaborative research projects both within and outside the university. What do you focus on to ensure that these collaborations run smoothly?

I have worked across almost every area of life science—starting in medical school, then moving into experimental biology, and later into ML. Drawing on this experience, I see my role in collaborative research as that of a ‘translator,’ helping to connect researchers from various fields. At kickoff meetings, I focus on mediating between participants and building consensus, and I make it a point to join all subsequent online meetings as well.

I believe the key to driving any project forward is to hold meetings about once every two weeks and to provide appropriate guidance to keep the project on track.

The same approach could be valuable in teaching students as well.

I think that’s true. In research, personal motivation and the sense that something is ‘interesting’ are very important. I value a style of mentoring that supports people when they encounter problems and works together with them to find solutions. I want students and early-career researchers to take on new challenges and pursue research that excites them, and I hope to help make it easier for them to take on those challenges.

● ● Off Topic ● ●

You seem to be juggling quite a number of projects and collaborative research initiatives. How do you manage your schedule?

I have about eight to nine meetings a day, and in between, I work on papers and grant applications. However, the most enjoyable part is having discussions with researchers and students.

That must be a big source of motivation for your research.

Yes. When I conduct experiments on my own, I can only explore about three things at a time. However, with collaborative research, it feels like I can expand my exploration in many directions. It’s like an ‘extended intelligence.’

That’s certainly one of the joys of collaboration.

Recommend

-

Creating a Flourishing Society with Novel Cultivars of Fruits: Integrating Molecular Genetics, Statistical Genetics, and Data Science for Efficient Fruit Tree Breeding

2023.09.08

-

Children-centered support and school operations: On the occasion of the founding of the Children and Families Agency

2023.02.15

-

Shedding Light on the Public Health Nurses Working at the Front Lines of Disaster-Stricken Areas

2022.12.07