Many women may hesitate to see a doctor simply because of a painful period. But what if that pain not only lowers their quality of life (QOL) on a daily basis, but also increases the risk of infertility in the future?

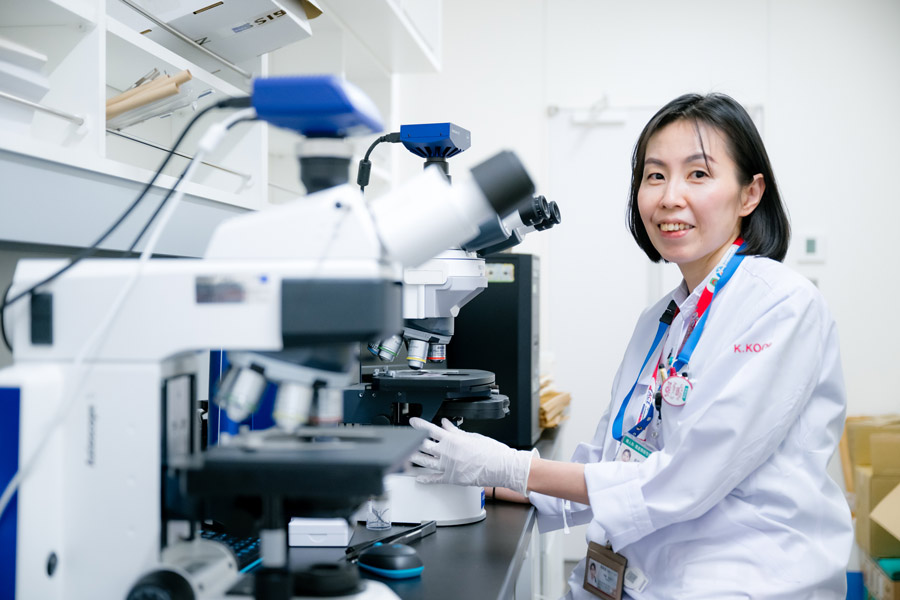

Professor Kaori Koga of Chiba University’s Graduate School of Medicine, who began her career as an obstetrician-gynecologist, is now dedicated to researching endometriosis—a leading cause of menstrual pain. She also plays a key role in launching a new reproductive medicine center, nurturing future medical professionals, and raising public awareness.

Research to conquer endometriosis—and to live with it

You are involved in a wide range of activities, including clinical work, research, education, and public outreach

Compared to researchers who focus on specific diseases, my work might seem a little hard to grasp as a whole (laughs). That said, the core of my research has always been endometriosis. It is a condition in which the endometrial lining, which normally forms inside the uterus, develops outside it. This can cause severe menstrual pain and lead to infertility later in life.

Many people think that “menstrual pain is normal“ and hesitate to go to the hospital. But it could cause infertility, and it shouldn’t be left ignored.

Exactly. Not all menstrual pain is caused by endometriosis, but if the pain is severe, I strongly recommend seeing a gynecologist. Pain that interferes with your daily life should be properly addressed, and endometriosis may impair ovarian function.

Is endometriosis curable once you visit a hospital?

That’s precisely the field of my research. Many scientists around the world are trying to identify the causes of endometriosis and develop treatments. But a complete cure is still far off and will take time.

Unlike cancer, endometriosis is not life-threatening on its own. So, in addition to studying how to cure the disease, researchers like me also focus on how to alleviate the related symptoms—like pain and infertility—so that patients can live well with the condition.

What kinds of approaches are available?

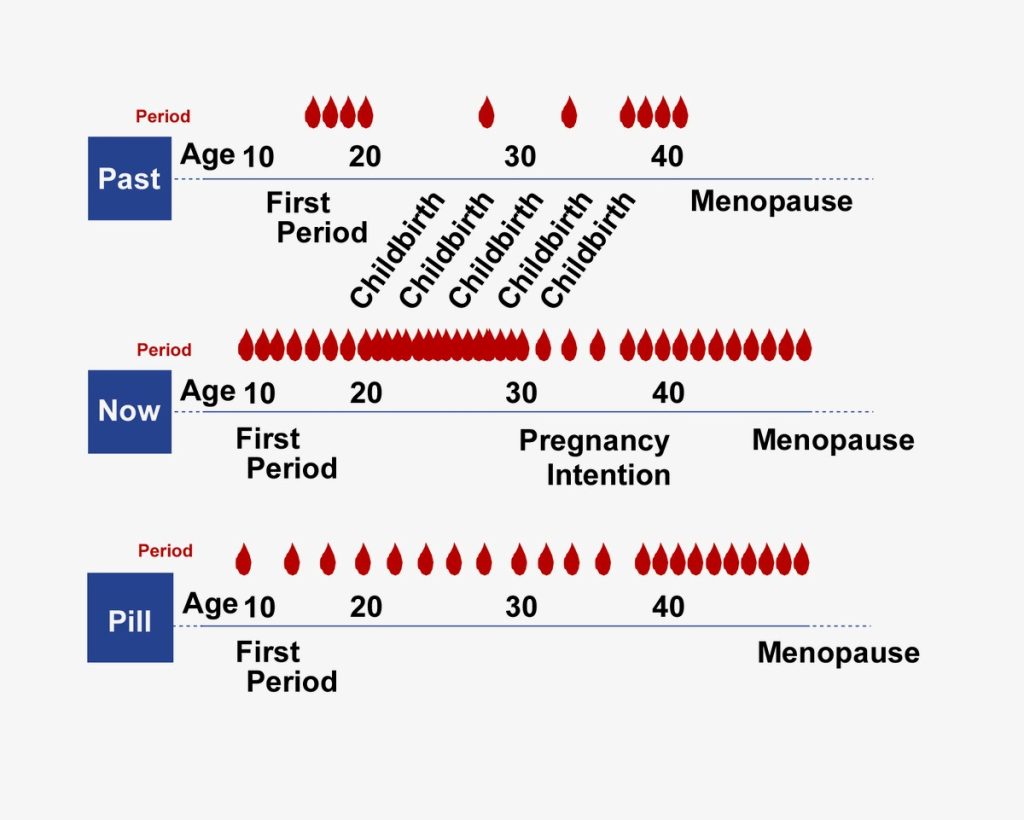

One widely used method is to stop menstruation by taking contraceptive pills* that suppress the growth of the uterine lining. Compared to women 100 years ago, modern women experience menstruation about ten times more often—due to earlier first period, later childbirth, and fewer children overall.

* The pill: To be precise, the pill refers to a contraceptive drug, and the therapeutic pill for pain is called a ‘low-dose estrogen-progestin preparation’ in Japan.

Another approach is to address the pain itself. While painkillers are one option, we are currently conducting clinical trials in collaboration with a startup that has developed a medical device designed to relieve menstrual pain. The device is being tested particularly for women who find medications ineffective, who experience disruptive side effects, or who are undergoing fertility treatment and cannot use pills. We hope this will become a new option for them.

What can be done to prevent future infertility?

We still don’t fully understand how endometriosis affects eggs and leads to infertility. Therefore, my lab conducts experiments using mice and cell cultures to uncover the underlying mechanisms and explore ways to prevent them.

We are also analyzing big data—including genetic and gut microbiome information—to identify differences between women who develop infertility and those who do not, as well as between those who respond well to medications and those who do not.

Nowadays, many women use wearable devices and apps to track their health data, including basal body temperature and ovulation. With proper safeguards to ensure anonymity, we are now able to collaborate with companies to conduct joint research using data on a scale far beyond what we could collect in a university hospital.

Why Gynecological Conditions Are Overlooked—and Misinformation Spreads

Either way, if you have severe menstrual pain, the first step is to see a gynecologist. However, many women don’t seem to have a regular gynecologist.

That’s right. Whether it’s menstrual pain, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), or menopausal symptoms, gynecological issues rarely receive public attention, and many people end up silently enduring them. Last year, a morning drama on the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) featured a scene in which the main character was suffering from menstrual pain. It was widely praised as groundbreaking. This stands in stark contrast to conditions like hay fever, which people can talk about freely in any setting and for which they readily visit an ENT doctor.

When it comes to gynecological issues, people often rely more on advice from family and friends than from medical professionals. This leads to a major problem: misinformation not based on medical knowledge, or one person’s anecdotal experience, can easily spread like an urban legend.

Raising awareness is essential for delivering accurate information, but no matter how many lectures I give, there is a limit to how many people I can directly reach. And people naturally tend to trust the words of those close to them. For example, if a friend says, “I went to the gynecologist because I was in pain, but the doctor told me it was nothing serious,” others might conclude, “If I go, I’ll just be dismissed too.”

That’s why I believe it is important for every doctor on the front lines not only to treat the patient in front of them, but also to communicate with care and clarity. Rather than simply stating the fact, “There’s nothing to worry about,” it’s better to add something more empathetic, such as, “I’m glad it’s not a serious condition.” That way, when patients share their experiences with others, the doctors’ message is less likely to be misunderstood.

Integrating Public Health, Psychology, and Economics to advance society and women’s health

I understand you are also conducting research from a public health perspective

That’s right. Since I am not a public health specialist myself, I’ve been collaborating with specialized laboratories by dispatching members of my research team. Until recently, the medical fees for treating menstrual pain remained the same regardless of whether hormone therapy was prescribed. However, in 2020, the government introduced a new reimbursement system that allows us to charge an additional fee if hormones are prescribed with a proper explanation. In response to this change, we launched a public health study to examine whether the revision in medical fees has led to an increase in hormone prescriptions.

As it turned out, prescriptions did rise following the introduction of the surcharge. This finding provides valuable evidence that policy decisions can influence how doctors make treatment decisions. While the additional cost to patients is a few hundred yen, the improvement in QOL can be substantial over time. Considering the potential to reduce future infertility risks, I believe this is a highly beneficial policy overall.

Menstrual pain, PMS, and menopausal disorders affect not only individuals and their families, but also have broader socioeconomic impacts. Yet, these effects are still largely invisible to the public. By quantifying the damage—both to individuals and to companies that employ women—we can help society recognize that this is a real and pressing issue. And that awareness is the first step toward creating momentum for change.

More and more companies are introducing menstrual leave, but the utilization rate seems to be low.

Yes, that’s true. While companies want women to take advantage of the policies they have introduced, in reality, they are rarely used. That’s why we are researching what kinds of systems and considerations would make these policies more accessible and easier to use. Our aim is to encourage behavioral change, so this is interdisciplinary research that also draws on insights from psychology and economics.

That’s quite a bold way to straddle academic fields.

There are many things I’m interested in and want to pursue—basic medical research, clinical research, social medicine, including public health, and not just research on endometriosis, but also awareness-raising activities for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Of course, I can’t do any of them alone, and I’m not the type to charge forward on my own with passionate intensity.

But if you keep saying things like, “I’d love to try this, but I wonder if it’s possible,” eventually, someone will hear you and offer to help. For example, when I said I wanted to raise awareness about the HPV vaccine, one responded, “I don’t know much about HPV, but maybe my experience promoting rubella vaccine awareness could be useful,” and kindly offered their support.

Even if I can’t immediately take the next step in all the things I want to do, someone else might help connect the dots—or I might be able to connect them myself down the road. That’s why, instead of hesitating over whether what I’m saying has value, I just keep putting it out there. My goal is to build a strong base of evidence to support women’s health and QOL, and to help create a society where accurate, trustworthy information about gynecology is readily accessible.

● ● Off Topic ● ●

Could you tell us about the Reproduction Support Center, where you were appointed as director last year?

Originally, male infertility was treated at the urology department and female infertility at the gynecology department. What makes this center unique is that it brings both departments together, enabling doctors to share medical findings between them accurately when treating a couple.

You describe it as a ‘one-stop’ center.

Yes. For example, if someone with diabetes is concerned about whether it’s safe to become pregnant, our center can coordinate communication between the diabetes specialist and the obstetrician to provide appropriate treatment guidance.

We also have nurses who specialize in infertility or genetic diseases, as well as staff members who are well-versed in medical cost subsidies. It’s a multidisciplinary team that supports patients so they can make informed decisions about their reproductive health.

Chiba University Hospital Reproduction Support Center

https://www.ho.chiba-u.ac.jp/hosp/section/reproduction/index.html

Recommend

-

Building a Future Where Nursing and AI Coexist: Harnessing Data to Deliver Better Care

2025.12.26

-

iPS-NKT Cell Therapy Paves the Way for Revolutionary Cancer Treatments: Bridging Basic Research with Practical Application

2024.11.01

-

A Day in the Life of a Sports DoctorProfessionals behind the world’s most prominent sporting events

2023.04.13